Misogyny cancelled the actors in Hollywood and Bollywood—But in Tollywood they are rewarded: Sivaji controversy

By Kausalya Rachavelpula

Film industries reflect the values they choose to protect. Nowhere is this clearer than in how they respond to misogyny and abusive conduct by their stars. In Hollywood and, increasingly, in Bollywood, public misogyny has become a professional liability. Careers stall, roles disappear, and institutions withdraw support. In Tollywood, by contrast, similar behaviour is frequently normalised, and in some cases, followed by increased visibility and opportunity.

What makes this contrast even more troubling is the language used to defend misogyny in India. Almost every time a woman is harassed, abused, or publicly shamed, a familiar accusation surfaces: “This is because of Western culture.” Women’s clothing, independence, speech, or confidence are blamed, while the perpetrator is excused as a product of “tradition” or “values.”

Yet this argument collapses the moment we look at how Western film industries actually behave.

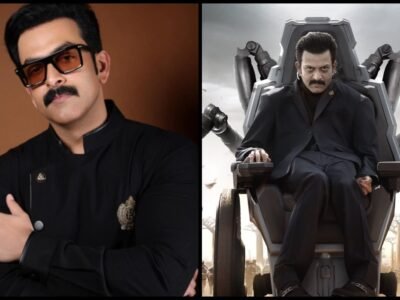

The recent controversy surrounding Telugu actor Sivaji, best known now for Court: State vs A Nobody, exposes this contradiction clearly.

At a recent film event, Sivaji made unsolicited remarks about women’s clothing, framing women’s dignity and respect around how “covered” they are. The language he used was widely criticised as derogatory and moral-policing. This was not an isolated slip. During his stint on Bigg Boss Telugu, Sivaji repeatedly exhibited misogynistic behaviour, berating women contestants, questioning their character, and at one point stating that if a daughter behaved similarly, he would “stomp her on the neck.” These statements were broadcast publicly, recorded, and remain available.

Despite this documented pattern, Sivaji was cast in Court after Bigg Boss. The people on social media are criticising Nani who is the producer of Court: State vs A Nobody for casting him. The backlash today is therefore not about discovering something new, it is about an industry choosing to ignore what was already visible. As a result, criticism has now shifted to the producer who gave him the opportunity, because the decision itself reflects a deeper industry mindset.

Even senior actors like Balakrishna, Chiranjeevi, Nagarjuna, ANR and Chalapathi Rao have faced criticism in the past for making deeply inappropriate and misogynistic remarks in public forums; however, sustained backlash and changing public scrutiny eventually led them to stop making such comments.

Balakrishna made terrible misogynistic comments about what he should do to heroines. Chiranjeevi called his home girls hostel and wanted his son Ram Charan to have a son for carrying his legacy. Even when many actresses like Alia Bhatt, Kareena Kapoor, Keerthy Suresh etc., have been doing just like many other male heirs of cinema celebrities. Nagarjuna commented on Sobhitha inappropriately, given her age, at a huge public gathering. The same was done by Akkineni Nageshwara Rao on Tamannah Bhatia years ago.

This is where Tollywood fundamentally differs from Hollywood.

Hollywood has increasingly shown that misogyny is no longer treated as a “personal opinion” or a cultural excuse once it is documented. Over the years, several prominent figures have faced serious professional consequences after allegations of abusive or misogynistic behaviour surfaced.

Actor Johnny Depp lost major roles, including in the Fantastic Beasts franchise, following allegations of domestic abuse by Amber Heard. Text messages revealed violent and misogynistic language, triggering intense public backlash. The case remained highly polarised, with different legal outcomes across jurisdictions.

Russell Brand, known for a long history of misogynistic jokes and comments, later faced sexual assault allegations. Several projects were dropped and public scrutiny intensified, although the allegations remain legally unresolved in recent years.

Comedian and actor Louis C.K. admitted to masturbating in front of female colleagues without consent. His confession led to cancelled shows and lost deals. While he later attempted a return, public response was mixed.

Singer Chris Brown, a Hollywood-adjacent celebrity, has a documented history of domestic violence and repeated misogynistic behaviour. Despite ongoing criticism, his career continues, largely due to sustained fan support.

Actor James Franco faced accusations of exploiting female students and engaging in inappropriate sexual behaviour. These allegations resulted in a lawsuit settlement, a sharp career decline, and fewer major roles.

Hollywood’s broader response reinforces this pattern. When Mel Gibson’s abusive phone calls were leaked in 2010, and he later pleaded no contest to domestic battery, he was dropped by his agency and sidelined for years. Armie Hammer’s career collapsed after leaked messages dehumanising women surfaced, followed by coercive behaviour allegations. Studios cut ties without cultural justification. Similarly, Shia LaBeouf lost industry support after abuse allegations and partial admissions.

The pattern is clear: when misogyny becomes visible in Hollywood, the system acts against the perpetrator, treating such behaviour as professionally disqualifying rather than culturally defensible.

The pattern is unmistakable: when misogyny becomes visible in Hollywood, the system reacts against the perpetrator.

Bollywood, though historically slow, has also begun to follow this trajectory. During India’s #MeToo movement figures such as Sajid Khan and Alok Nath were removed from projects, banned by industry bodies, and sidelined after multiple women came forward. These actions were not framed as attacks on Indian culture. They were acknowledgments that abuse and misogyny damage the industry’s credibility.

This is why the common Indian refrain, “This is Western culture corrupting us,” rings hollow.

If misogyny were truly a Western import, Hollywood would be defending it.

Instead, Hollywood penalises it.

Tollywood, however, continues to operate in reverse.

Here, misogyny is often reframed as “Indian values,” while accountability is dismissed as “Western influence.” Actors who demean women publicly are defended as outspoken or traditional. Fan culture rallies to protect them. Victims are interrogated, mocked, or blamed for inviting attention. The industry closes ranks, not to question the behaviour, but to preserve male authority and box-office certainty.

In this environment, misogyny is not a risk—it is a credential. It signals dominance. It appeals to a certain audience base. And as long as it sells, it is rewarded.

The Sivaji episode illustrates this contradiction painfully. His behaviour is neither subtle nor accidental. It is recorded, repeated, and consistent. Yet instead of being sidelined, he was given a prominent role after Bigg Boss. The outrage today is notable precisely because it is unusual.

The truth is uncomfortable but simple.

Hollywood and Bollywood, imperfectly, inconsistently, and often belatedly, have begun to treat misogyny as a professional liability. Tollywood still treats it as cultural authenticity. And while Indian society rushes to blame “Western culture” for moral decline, it ignores the fact that Western industries are actively dismantling the power structures that enable abuse, while parts of Indian cinema continue to reinforce them.

Cancellation is not about outrage.

It is about boundaries.

And until Tollywood decides that women’s dignity matters more than male stardom, those boundaries will remain dangerously skewed.