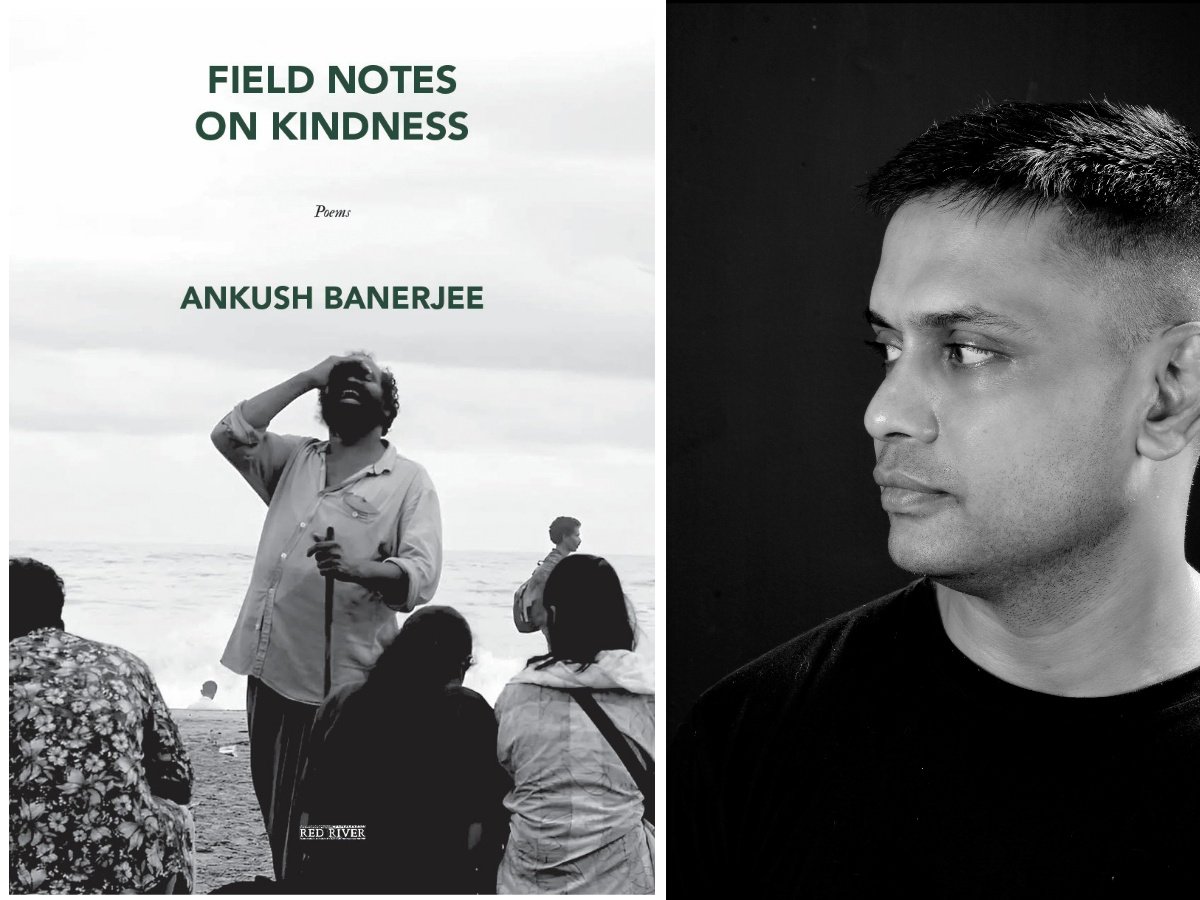

Ankush Banerjee’s Field Notes on Kindness illuminate that nebulous

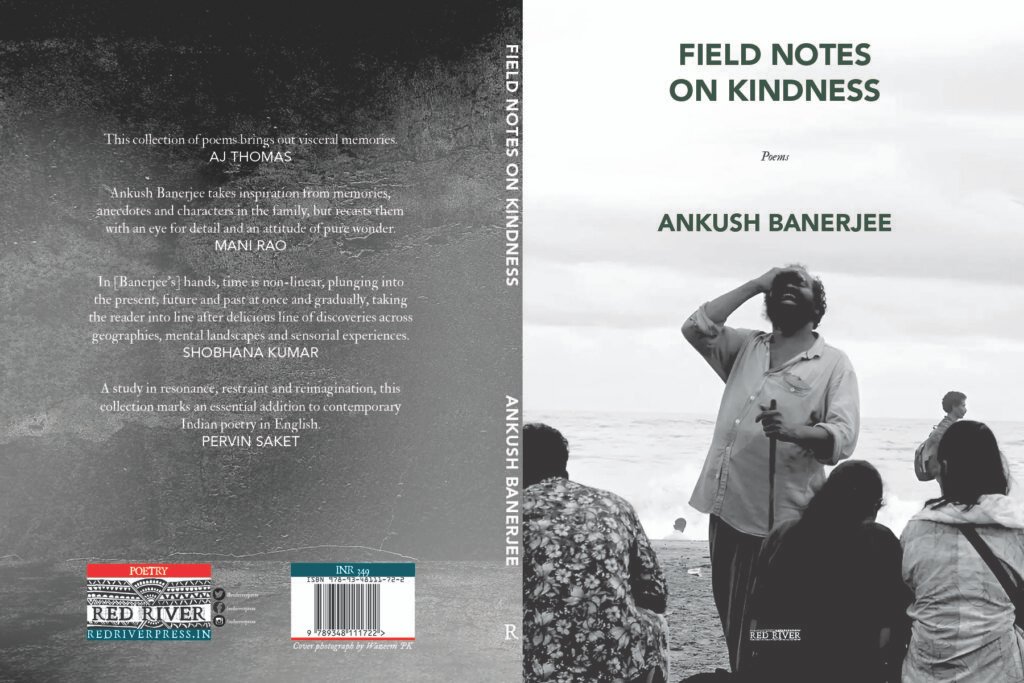

spaces within ordinary human acts, where kindness is found, reinforced, lost, and perhaps found again. Fridaywall is delighted to feature poet, scholar, writer, Ankush Banerjee’s Fieldnotes on Kindness, Red River Press, 2025 – Jhilam Chattaraj

Ankush Banerjee is by turns, a serving Naval educator, research scholar in masculinity studies, practicing poet, book reviewer, and reviews editor at Usawa Literary Review. He has written award-winning essays on Ethics and Leadership, research papers, short stories, and of course, poetry. His first collection of poems, An Essence of Eternity, was published by Sahitya Akademi in 2016. His latest book, Field Notes on Kindness, comprises poems written over the last eight years, and reflect his preoccupation with themes of memory, loss, family, and the understandable imperfections of human relationships.

Over the years, he has successfully juggled both his diverse roles and passions. He is a three-time winner of the United Services Institution Gold Medal Essay Competition (2015, 2018, 2021), for his essays on Ethics and Leadership. His poems have been widely published in national and international journals. Given that ethics essentially deals with the question of human conduct towards the Other, one can discern in his poems, more than anywhere else, a conscientious ethical concern examining, explaining, and even nourishing the vulnerabilities of human conduct. Likewise, his dissertation explores the idea of how emotion/affect can empower men and masculinities to resist dominant, discursive, hegemonic ideals, and forge more constructive relations with the Other, through close analysis of contemporary Indian English fiction. A similar passion drives his contributions towards curating and showcasing gender sensitive books for Usawa, one of India’s foremost online literary feminist magazines.

Speaking of his passion for poetry, he recalls how it all began during the rigorous training time at the Naval Academy when he was 18-20 years old. While he was always passionate about literature (novels, poetry) in general, given the regimentalised routine, there hardly used to be time to read recreationally. Novels were out of question, given that it required prolonged engagement with a text. Poetry, however, could provide an escape given its potential for deep emotional impact in short doses. He recalls reading a poem in the classroom, and then turning favourite lines in head: “tell the truth but tell it slant”, “let us go then, you and I”, “To force the pace and never be still”, savouring their somewhat illicit sweetness, amidst the hard routine. That’s where it all began.

His other accolades include winner of the 2023 National Poetry Competition (organized by the National Defence Academy), 2022 Spotlight Runner-up Poet for Eclectica, the 2019 All India Poetry Prize (III), and Commendation Awards from the Chief of the Naval Staff and Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief Southern Naval Command in 2023 and 2025, respectively.

His poetry is marked by emotional restraint, and confessional motifs, which implore the reader to simultaneously look within, and look beyond.

His latest collection of poems in Ankush Banerjee’s Field Notes on Kindness illuminate that nebulous

spaces within ordinary human acts, where kindness is found, reinforced, lost, and perhaps found again.

Mani Rao, the author of the recently released, So That You Know, in her blurb, highlights how in these poems, “inspiration arrives from such usual sources as characters in the family and conversations with friends, but is flipped by the poet’s sense of wonder and detail – which is also a definition of kindness”. Pervin Saket, whose forthcoming book, A Theory of Knots, draws attention to Banerjee’s “gift of turning familiar everyday moments into excavations of personal and social histories”.

The poems attempt to ambitiously trace where, to quote Julian Barnes, “the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation”. The poems in this book seem on the surface, to plumb the poet/speaker’s history, loves, losses, and vulnerabilities. What emerges though, is not a personal journey, or rather not only a personal journey, but a palimpsest of past and present, of imperfect articulation and

turbulent affect, framed in and through the precision of language. It is language – shall that be the poetic line, the pause, the enjambment – which seeks and illuminates those indefinable qualities of kindness, empathy, and even melancholy, amidst the messy, delicate crevices of human relationships. One finds fathers, mothers, grandfathers, grandmothers, a wailing son, lovers, and even cats in these poems – each of these fleshed and boned, in their own sweet vulnerabilities and all too human imperfections. The poems also seem to suggest that kindness is needed most when it is deserved the least. Perhaps, this is where the book derives its title from.

Here are a few excerpts from Ankush’s latest book, Field Notes on Kindness

Sometimes after-burn is worse than slow-burn

The evening before, when I got drunk, and you rescued

me from a bunch of guys for burning a 10 rupee note,

imitating The Joker, for saying, “its only money

that you want”, drunkness making something glorious

of second-grade contempt, and that razor punch

missed my face because you pulled

me harder than my weight, and later, waiting

for the bus, we sat in squalor painted in moonlight,

and men smoked bidis around us, played cards,

jerked off thinking of what to fuck next,

you fearlessly ran your hand over a scabies-ridden

dog’s head which had come to us for food, saying,

sometimes all we need is affection,

and the bus arrived and we had no biscuits

to give, so we fooled ourselves into thinking,

affection will put it to sleep, and

as the bus whirred past, and the night grew into

yearning the shape of steel rods and sweat smells,

you described to me the exact moment your wife

had confessed she had cheated, not once or twice,

not for sex, not for lust, not even for filling

an affection-sized hole left in her at

childhood, and how you had been making a

presentation, and you had wanted to crush the laptop

and throw it at her face, but all you managed

was to put your hands in your pocket, a slow

burn tiptoeing up your spine, tingling your ears

and all you did was to let the marriage cage open

like letting go an anchor into water

its azure weight being swallowed, and the

bus horn pierced the night, pierced

the veil of language we use to birth

the world in, and what you said was,

my palms smell of the dog, my palms smell

of the darkness of the dog.

■■

Field Notes on Retrieving Lost Things

(for Tia)

Note one, or how to discover when to not let go.

I am massaging varicose-ridden grandmother.

Relief uncoils her insides like bloodroot’s petals.

She says, I will haunt my sons

if they make a Mall where is this house is,

& I ask how, heart’s tongue pulsating

a story’s horizon,

she says, after I die I will come back

as a crow, perch on that Jamun Tree,

pointing to stained-glass windows, still there

in it, a frog-shaped hole

from whose belly

you & I

scooped moonlight slashed by fireflies.

Note two, or making a prayer from what is left to us.

After you left, your name was shards

roofed from my mouth. I spat

glaciers of silence. Because all my friends

are make-believe, resemble you,

wear white-rimmed specs, a ponytail, & full-blooded laugh.

We play the same games – hopscotch & scrabble, hide &

seek, & hand-cricket. I win all of these &

we go cycling. Past Mintu’s grocery shop where

you flick bubble-gums & lozenges.

Through lanes & alleys, scissoring puddles,

squeezing reflections of mid-flight crows

from brown surfaces.

Note three, or retrieving without the hope of holding.

After you left, I kept water for crows in a cracked,

green bowl. Stray dogs drank from it &

sparrows and pigeons, & then crows,

who came, pecked at the water’s surface, cawed,

& flew away.

■■

Preparing for Another life

Before the anaesthesia kicks in,

for the last time – you are Long Distance Runner

no longer in Pre-Op

staring that dome of light –

to you a moon you want to touch

only because flying to it won’t need legs.

The body like a train’s whistle

the darkness of a tunnel

coiling around it. An attendant

joking about the birthmark they will cut

to place the screws in the socket.

The birthmark looks like a sparrow

about to fly. Before anaesthesia shatters

the bough of your body, before the

moon overhead is a mouth of darkness, you

pray they fill the space between dislocated hip

& future with what you heard but

could never hold

in that joke about a grackle

taking flight.

■■

Chaos Sonata

(Ogu & me)

0330 am. Vocal cord the size of

Eiffel crash. My ears. I

stuff my mouth

with a hand-grenade’s

worth of silence

before a hopeless soldier,

now surrounded, pulls the pin.

Somewhere in diaper-city, a war rages.

Trenches overflow with effluents.

Moonlight cuts us into shrill

Chaos Sonata heard

in this amphitheatre for three. We implode

so shrill, I swear I thought I heard you.

Now a days, I can’t hear you. I try. The

chasm between banality and grand narrative

is so small, no Feeding Pillow can sleep over it.

Empty bottles, nipples, Feeding Spoon nestle

in the Steriliser’s womb you forgot to turn on. For a brief

moment, there is stillness so white, I thought

I am in a cloud, free-falling into your throat

to embrace vocal cord sketched

in an arc of innocence. Mutual helplessness

& learning is the name of this game. Love was never

the deficit. Sleep was. Is.