From Bonded Labour to Brad Pitt – The Dark History Behind Fashion’s Favorite Natural Dye – Indigo, by Rajeshwari Kalyanam

As Indian indigo and textile crafts gain popularity on global luxury runways; it’s time to understand the colonial past and acknowledge the craftsmen in order to build a more ethical, inclusive, and sustainable future for fashion

Kolhapuri makes it to Prada, and Dior uses Lucknow’s mukaish embroidery in their Paris show – just a couple of the many instances where Indian crafts and textiles have been used by luxury brands without a line of credit. Recently, when Brad Pitt wore an indigo-coloured shirt – made using the Tangaliya weaving technique, an intricate handloom art form from Gujarat – in the movie F1, we rejoiced.

It is, after all, an Indian brand that made this beautiful shirt – a brand working with vanishing textile traditions. But one wonders if the wearer knows where it came from. It looked great on him, nevertheless. Let’s hope he knows! There is sweat, blood, and tears that went into making the exquisite garment. Does the fashion world, which is fond of indigenous natural dye indigo, know that it had been a colonial tool of oppression for a very long time in India? And does it acknowledge the burden of the dark past it carries? Do we know?

Knowing the history of indigo in India for instance has a larger impact on the way we live today, grow our crops, and respect our land for a sustainable future. Acknowledging the oppression and understanding exploitation is the first step for the fashion world towards adopting humanitarian practices for a better world.

Brad Pitt wore an indigo-coloured shirt – made using the Tangaliya weaving technique, an intricate handloom art form from Gujarat

Indigo in Indian Textiles and Colonial History: A Profitable Crop Turned Weapon of Oppression

The story of indigo goes back to the 17th century. It was already considered a profitable crop for rulers and was being forced upon much of India by the British government in the 18th and 19th centuries due to increasing demand in the world market. The British colonial rule in India was used to utmost advantage to exploit poor farmers, with the help of landowners – the zamindars – and the exploitative land settlement system introduced by the British.

An article in Al Jazeera from as far back as 2020 talks about the “Blue Gold” – indigo. It is the story of a fourth-generation indigo farmer from the South Indian village of Kongarappattu, who is reaping the benefits of extracting the natural dye from the Indigofera plant. It makes a passing reference to colonial times when “many Indian farmers were strong-armed by the British Raj into growing indigo instead of food crops. The dye was then bought by the Raj at unfairly low prices.”

“Strong-armed” is surely a mild word for all the atrocities faced by Indian farmers during the Raj. Celebrated author Amitav Ghosh, in his Ibis Trilogy, extensively refers to opium – yet another cash crop forced upon the farmers of Bengal, throwing them into poverty and hunger while the British amassed monumental wealth from the opium trade. Post the 1850s, with a decline in demand for opium, the focus shifted to indigo.

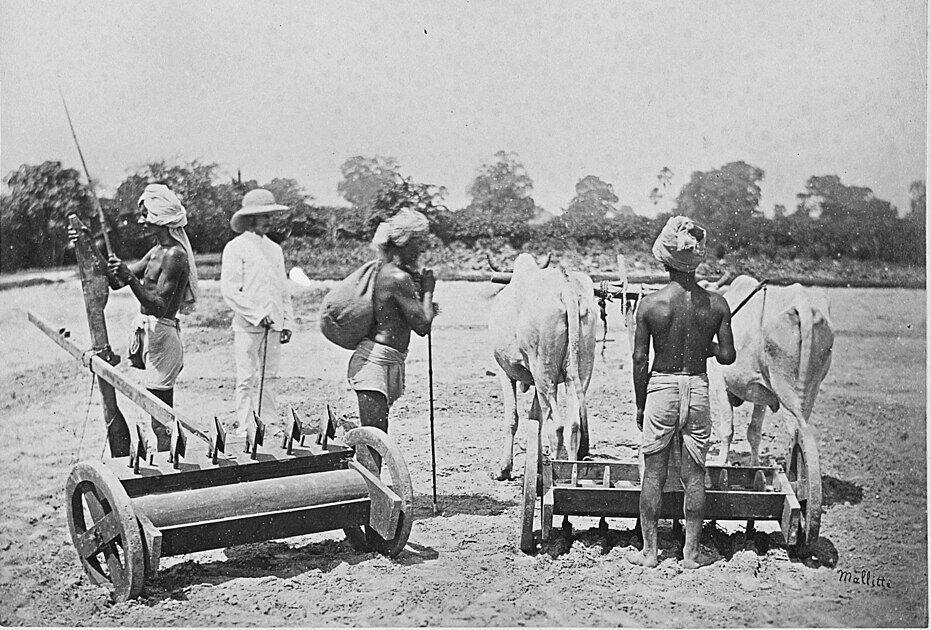

Indigo Farmers From Allahabad

Revolt in Bengal: The Peasants Fight Back

Stories of horror, intimidation, rape, and torture are kept vivid in memories in Bengal, alongside the glorious stories from the Peasants’ Uprising of 1859–60, when farmers of Bengal refused to grow indigo, boycotted taxes, and revolted against the planters. An Indigo Commission was constituted, and some of the planters then moved to Bihar.

Bengal’s indigo uprising had the support of intellectuals, which Bihar lacked, and hence it flourished in the region of Champaran.

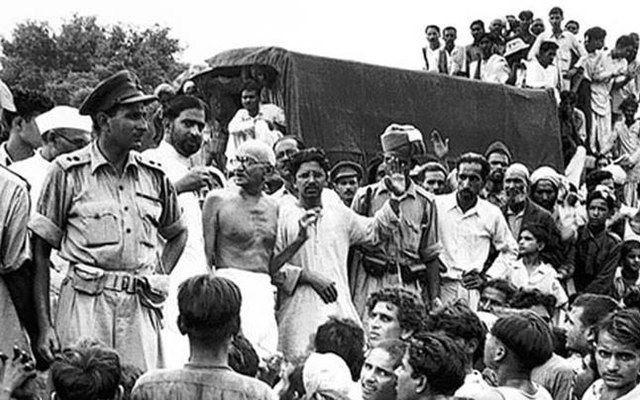

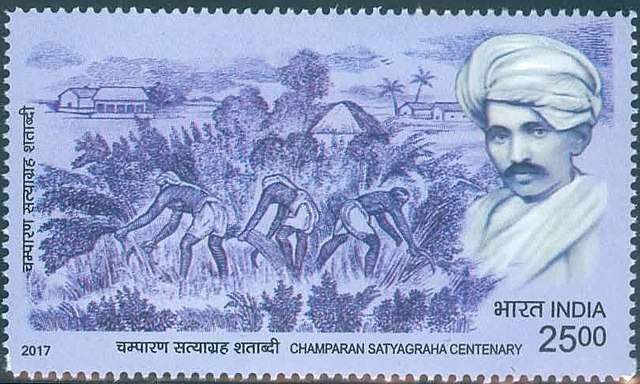

Gandhiji at Champaran in 1917

The Legacy of Champaran: Gandhi Steps In

In the 1850s, this region in Bihar – comprising Champaran, Saran, Darbhanga, Patna, Shahabad, Munger, and Tirhut – produced 30% of the total indigo crop production (P.K. Shukla in his paper Indigo Cultivation and the Rural Crisis in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century, 1988).

The infamous Teen Kathiya system in the region mandated that three parts of a bigha (in today’s terms, approximately 3,000 sq. yards) had to be reserved for the cultivation of indigo and sold to the planters (the Neel Sahibs) at low prices. This left the land infertile and the farmers poor and hungry – incapable of growing enough food crops. This went on for years until the Champaran Satyagraha, initiated by Mahatma Gandhi in 1916, led to the abolition of Teen Kathiya.

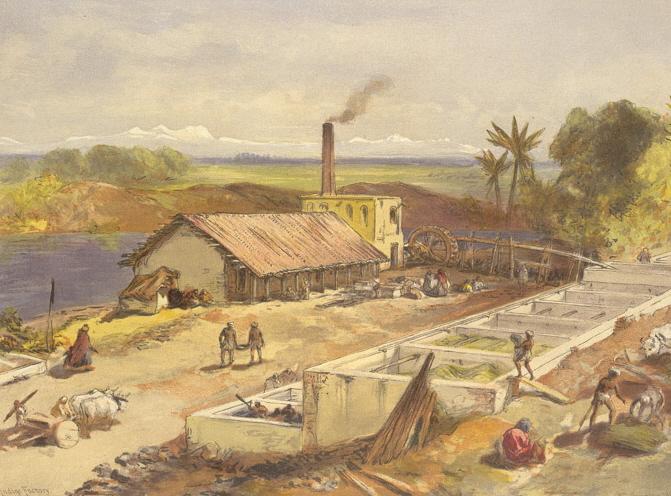

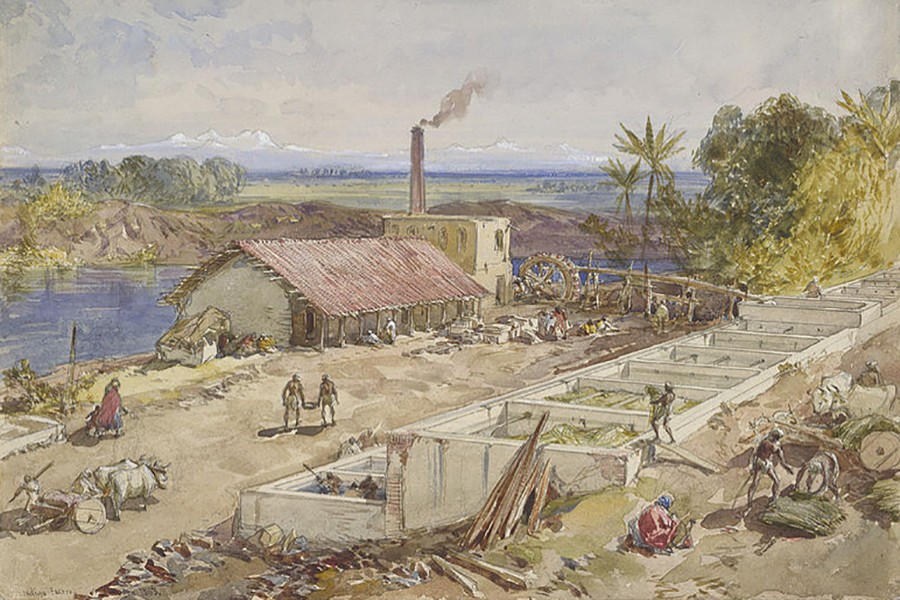

Indigo Factory in Bengal, 1860

Neel Kothis: Factories of Pain and Resistance

The infamous Neel Kothis – the indigo factories built on acres of land – are witness to atrocities on women and children, aimed at forcing farmers to grow indigo. These factories threw families into debt and turned them into bonded labourers. A few Neel Kothis still stand today in Bihar, as testimony to this ghastly colonial past.

These stories are tucked away in the pages of history – so far from the public eye that we now celebrate the natural dye in today’s fashion without even a blink of thought about its grim colonial history. However, it is kept alive in cultural contexts thanks to a few playwrights and authors. Without them, the collective history – of the oppressed Indian farmers and the colonial Raj – would have long been erased from our conscience.

Stamp Commemorating 100 Years of Champaran Indigo Farmer Satyagraha

The Komola Collective & Their Play Indigo Giant

Way back in 1858, playwright Dinabandhu Mitra wrote the Bengali play Nil Darpan, later translated into English as The Indigo Mirror, which played a significant role in highlighting the exploitation by British planters and aided the Indigo Revolt. In recent times (2024), a theatre company – The Komola Collective – created an English play with characters drawn from the Bengali original. The play, developed after extensive research by the team (with playwright and co-producer Ben Musgrave in the lead), is an interdisciplinary project that has toured the UK. The collective has played an active role in engaging local communities to collectively explore the legacy of indigo cultivation.

Leesa Gazi, co-founder and joint artistic director of Komola Collective, shared in an interview (Eastern Eye): “Indigo Giant not only talks about how the rebellion shook the British Raj; it also looks at the impact it has on modern society. It’s important for us to know how the world works, how oppression works, and how injustice and manipulation work.” She stresses the importance of understanding colonial history in the context of the debate on immigration, even.

Fashion’s Blind Spot: Appropriation Without Acknowledgement

That brings us back to the topic of history and its larger relevance in modern times and practices. When today someone wears India’s indigo as a fashion statement and endorses a dying handicraft – while it is important to preserve the craft – one must also understand the history. The garment not only carries the beauty and elegance of textile tradition and craft, but also the burden of the past – and the hard work of today’s underpaid weavers – that needs to be acknowledged.

The East India Company, followed by British rule, gradually destroyed indigenous crafts like textile manufacturing and reduced India to a supplier of raw materials. Today, when the Western world increasingly appropriates our textiles and handicrafts, introducing them as high-end luxury fashion without even a nod to the source – let alone any consciousness of the colonial burden they carry – it is hardly a matter of pride.

As the world of fashion moves towards sustainable fashion, India can offer thousands of handmade crafts and textiles that can inspire world-class designers. And this treasure trove has already been discovered. Hence, it becomes more urgent to provide cultural and historical context to the narrative, in addition to GI tags. The onus of giving back to the craftsmen and weavers – for the survival of the craft – also lies with Indian brands and the government first. We must not just sell the garment but ensure it carries with it its unique story and history – the glory and the gory.

Understanding what oppression is will help us make this world better. Especially in the global fashion scene – the sweat factories of Bangladesh driving fast fashion, the craftsmen and weavers of India who dwell in poverty while keeping dying crafts alive, and the connoisseurs clothed – are examples of modern-day exploitation. It is the responsibility of entrepreneurs, designers, and luxury brands to not repeat the past and to include the actual creators in their glory and profits.

To Read More Stories

Subscribe to Fridaywall Magazine