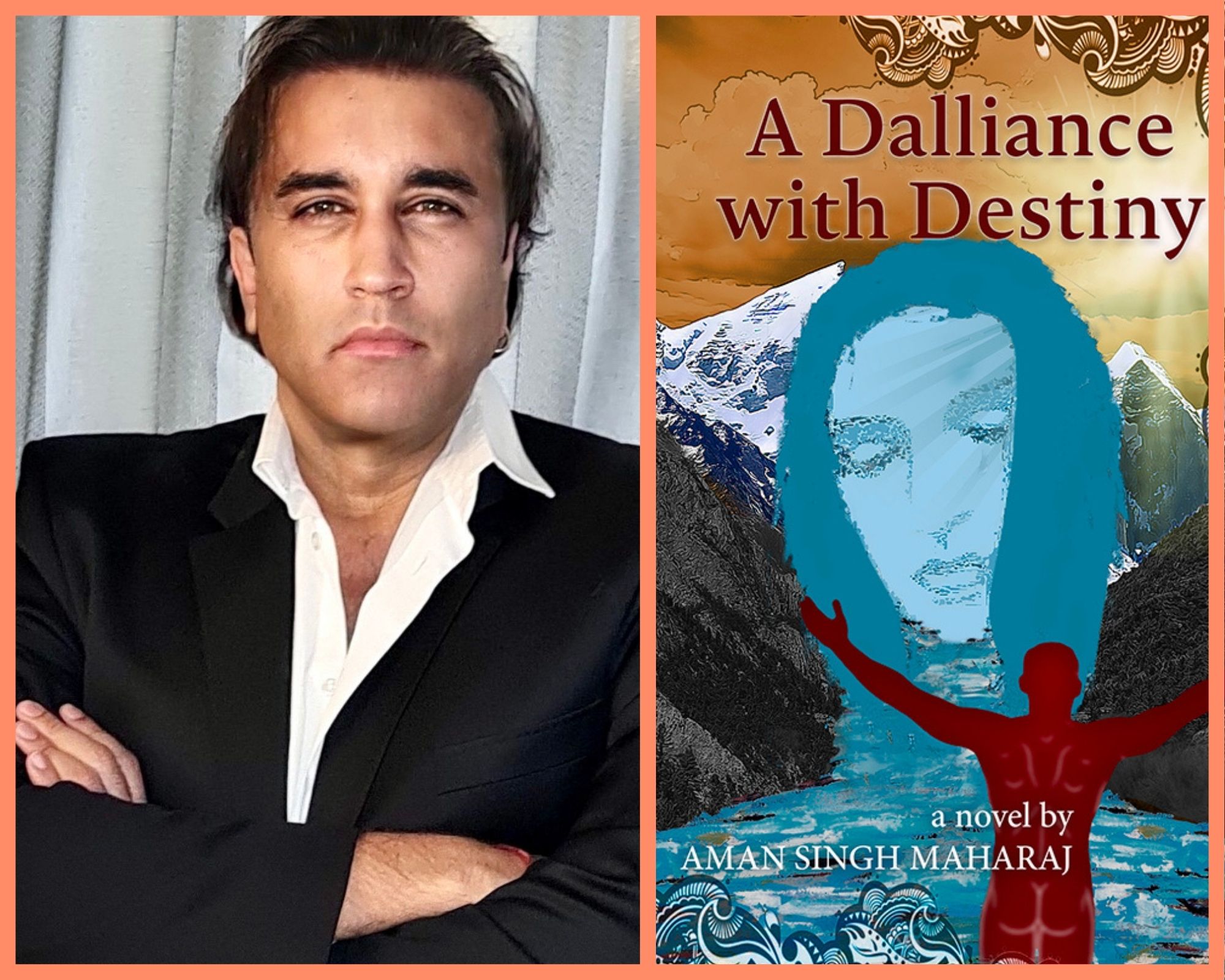

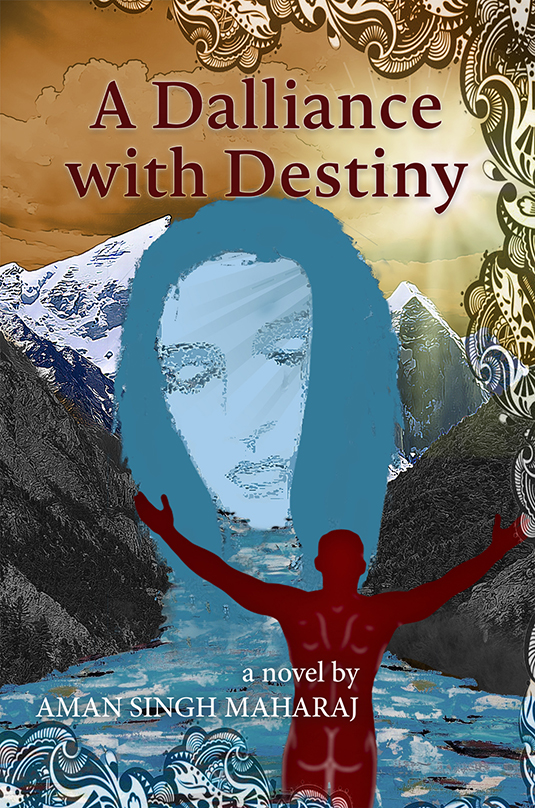

A Dalliance with Destiny published by Austin Macauley takes us on a mystical journey to India through the eyes of Indian origin author Aman Singh Maharaj from Durban, South Africa. He comes with a large extended family, and lives in a home overlooking the picturesque Indian Ocean where the idea for his debut novel took shape. Also spending a considerable amount of time in India, annually, he considers himself a nomad, travelling the world. Taking an avid interest in anthropology, he never ceases to be enthralled with the sheer kaleidoscope of cultures, diversity and architectural marvels that the world has to offer. And, this reflects in his work A Dalliance with Destiny, which is touted to be a literary debut that dissects the human condition with extraordinary attention to detail.

Here’s a bit of a pre-praise for the novel that is being well received in south Africa before releasing in India, where much of it is set.

Here’s a bit of a pre-praise for the novel that is being well received in south Africa before releasing in India, where much of it is set.

“The human condition is dissected in all its complexities with a sharp scalpel, where we sometimes feel a sense of discomfort because nothing is quite safe. And, then, just as rapidly, it suddenly points us towards our own soulful compasses. The intertwinement of humor and pathos cuts close to the bone, but leaves us with a blush in its wake.” – ZP Dala, Writer

“The narrative reminds one of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales – the bawdy unraveling of the archetype’s sex life juxtaposed against his quest for spiritual enlightenment as a pilgrim.” – Prof. Lindy Stiebel, Head of Department of English Literature at University of Natal, Durban.

“A commentary on the life of a young man in search of his epic life story, one roots for the main character, yet hates him in equal parts. This intrepid piece of writing brings to the surface a litany of oscillating emotions, for there is nothing ordinary about the lead character’s journey. There is no moment of blandness here.” – Aziz Hassim, Writer.

Here’s a excerpt from the book A Dalliance with Destiny published with permission from Austin Macauley

A young taxi driver ran towards me, smiling. “Please, Sirrr … I am Raju. You are coming with me, yes?” he asked. The red betel nut juice that stained his lips and tongue dripped down his jowls, giving him an even more unusual look. His hair, as most taxi drivers preferred, was slicked back with copious amounts of oil, and had no particular parting. His moustache was not brilliant by Indian standards, but had been carefully shaped with the upper half shaven to leave a thin line above his lips. It was what one would call ‘Bombay Ghetto Chic’, making him look like an Indian version of a young Marlon Brando.

I saw Birju preparing to be the toughie, as if he were ready to bargain. I knew, though, that he waited for me to stop him, as I always did. His strongman tactics were only for me to bear witness to, as he never could follow through. I duly signalled to him that I would handle the bargaining, if any were required. “Colaba … kithné?” This was my staccato way of asking for the fare to the area. “Please, Sirrr … for you, only eight hundred rupees. I got numburrr vunn music in car. All tiptop sounds,” said Raju, looking at me, while I simply stared at him, not replying. “Firshtah claashah,” he added. (I just loved the way he had said ‘first class’.)

“Saala, behanchod, Hijda ki aulaadh, cheater!” muttered Birju, swearing colourfully under his breath, incongruously calling Raju a ‘thieving, bastard, sister-fucker and the offspring of a eunuch’. Birju tried to make the vein in his temple bulge.

I didn’t respond, waiting for a decrease in Raju’s price. “Sirrr … for you I have special price. Only six hundred rupees,” pleaded the bewildered driver, rapidly dropping his initial rate at my silence, while I continued staring at him.

“Tell him five hundred rupees. He can take it or leave it,” continued Birju, whispering under his breath, which I ignored again, as he was always kanjoos about money.

My stoic silence compelled Raju to decrease his price even further. “Sirrr … you carry heavy-heavy luggage. Please, Sirrr … five hundred rupees only, Sirrr. Best price. You first customer this morning. Good luck for me, good luck for you. We all happy-happy, yes?” cried the driver.

I indicated my bag to Raju as my way of acquiescing on his rate. He grinned. My insides warmed. I had a sneaky suspicion that the Cool Cabs company would’ve been cheaper and more comfortable, but I was ok with that. I truly wanted Bombay style authenticity. These seemingly tiny men had a hidden

physical power, for he deftly lifted my suitcase and placed it on the carrier atop the car with a strength that belied his size.

The inside of the taxi smelt like all the black and yellow cabs in Bombay did: a mixture of incense sticks, sweat and stale spices, all trapped in velvet upholstery. Raju had a statuette of Lord Ganesha on his dashboard, complete with a miniature garland and a dot on its forehead. He blared some old music, a seventies tune by pop singer, Usha Uthup, rendering Dum Maaro Dum in her usual base voice. The strains happened to come from a cassette player that had probably seen better days, as the music tended to be legato at the most inappropriate of times. “Raju, please play song softly, ok?” I requested. “Me very tired,” I added, using a quaint local dialect of English as I gazed at the rundown shanties that thronged the trunk road into the city.

“No problem, no problem,” said Raju, although he didn’t lower the volume. Each time the song went into chorus, so did he. In tandem with this, he would suddenly increase the speed of his claptrap taxi, his own singing seeming to catalyse the extra pressure on the accelerator.

“Aréh, slowly, Raju! Dheeré chaloa!” I pleaded with him in poor Hindi to drive slowly.

“No problem, no problem, Sirrr. You from Africa, yes?” he continued, giving me a gummy smile, betel nut juice spraying onto the dashboard, while decelerating rapidly and simultaneously lifting one leg up so that he could dig at his toes, which were black with grime. The nails were thickened by some fungal growth and were a few millimetres too long.

I braced myself, re-swallowing the aeroplane food that had surged up my throat. I tried ignoring the driver’s personal hygiene habits and focused, instead, on how he had distinguished my nationality. It was a while before I realised that he must have glanced at the baggage tags. “Yes-yes … South Africa,” I replied, stressing my country.

“Very good, very good. Numburrr vunn kirkit team, they are having. Very good fielding. Numburrr vunn, numburrr vunn!”

“Raju, I support Indian team,” I said, testing his reaction.

“Thoo!” he spat out of the window, a bit landing on the rear windscreen from the backdraft. “Maadharchod haraamis! They go overseas and puts dhandhas for Goris and takes the firangi drinks and plays like choothiyas.” He seemed bitter about the Indian team’s fluctuating performances: men using cricket bats as extra-large dildos with willing White women.

The drive continued like this. Haphazard talk volleyed between Raju and me about cricket. We passed more slum tenements, which looked like oversized matchboxes with grimy facades, all dwarfed by huge billboards with painted faces of exotic film heroines. The shanties were huddled close together, as if in defence to the raging monsoon that unleashed itself in summer. I was reminded of a famous song about Bombay for those who had to survive its trials and tribulations and began humming it in my head … Yeh Hai Bombay Meri Jaan.

Birju listened to our banter, simply shaking his head as we passed the colourful suburbs from the airport to the hotel. Santa Cruz, Khar, Bandra, Mahim, Matunga, Dadar, Mahalaxmi, Bombay Central, Grant Road and Girgaon whizzed by until we finally reached Chowpatty Beach on the northern end of Marine Drive. I had opted not to take the shortcut through the new Worli-Bandra sea link, wanting to maximise the journey time. It was all about the experience. Here, I caught sight of the radiance of the Queen’s Necklace, the string of lights that curved into the distance and ended at Nariman Point, the very southern edge of Bombay, a make-out venue for young lovers. My heart leapt. Its residual cloud parted for a while, enchanted by the buzz of the city. I absorbed the urban landscape of Bombay, which I later saw had changed with the proliferation of even more mammoth flyovers that traversed the middle of the older roads, having

been erected to ease the tremendous traffic congestion.

We turned into Cuff Parade from the Marine Drive area and reached Colaba at five in the morning. The city had already come to life in certain areas. I had seen early risers walking towards Jogger’s Park in Bandra. Fat-fat ladies in tight- tight lycra pants and oversized t-shirts with higgledy-piggledy breasts. Rich-rich men in shorts with hairy-hairy calves and designer mineral water bottles in their left hands and well-bred German Shepherds on their leashes in the right. These pedigreed canines were a sharp contrast to the many wretched, ownerless dogs, which generally roamed Bombay’s streets.

Poor Marathi women employed by the Brihan-Mumbai Municipality, with saris wrapped in typical lower-class Maharashtrian fashion, without blouses, were already sweeping the streets with crudely made brooms, smiling at the ground. The falls of their shabby saris were wrapped tightly around their shins as they swept with a vigour that belied their advanced age. One had to give credit to these poor Indian workers. It seemed that they found happiness even in the most trying of circumstances. The elixir of life, perhaps, lay in the bowels of monotony. A humdrum existence that I was not akin towards living in India.

I loved Colaba. I loved its vibrancy. I loved its decrepit buildings and the ugly nakedness of their electrical wiring that hung out like the intestines of some gutted animal. I even loved its pimps who offered me girls for five hundred rupees a night while I walked the streets in the evening, who followed me with such dogged perseverance despite me never accepting their peddled wares.

We drove past Leopolds and Café Mondega, both establishments where I had brazenly picked up foreign women for brief moments of lust on previous trips. I had been through a whole number of ‘Dancing White Elephants’: backpacking female tourists from America, Brazil, England, Europe and Australia. I had indulged my carnal appetite to its maximum until I tired of it; weary of this anonymous sex in the stickiness of Bombay’s weather, cavorting on squeaking beds and feeling cheap, rough cotton curtains blowing against my face.

Admittedly, though, there was nothing quite as thrilling as romping with a French backpacker in her dorm room in some grubby inn in Colaba while she spoke words of amour in her mother tongue, and then being caught by her German and Italian roommates who then joined in the fun. I would feel like England in the eighteenth century, with my fingers dabbling in every country. It was so utterly grimy, so unreservedly animalistic. I loved it for the sheer aberrant filth of it all, screwing a bevy of international women in successive spurts while looking through a smudged window, out onto the gritty streets below. Bombay gave me an opportunity to fulfil my most pornographic of desires.